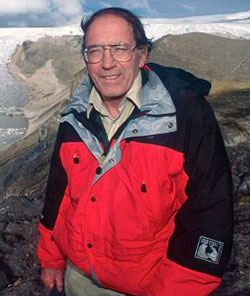

Mosley-Thompson specializes in the polar regions (both Arctic and Antarctic) while Thompson scours temperate and equatorial mountains in his quest for icy records. The team has built up a “frozen history of the Earth,” which they store at Ohio State University, home base for their research. This library of the Earth’s climate has helped the duo document the environmental connections between the low and high latitudes, yielding new information on how human activities may modify those connections.

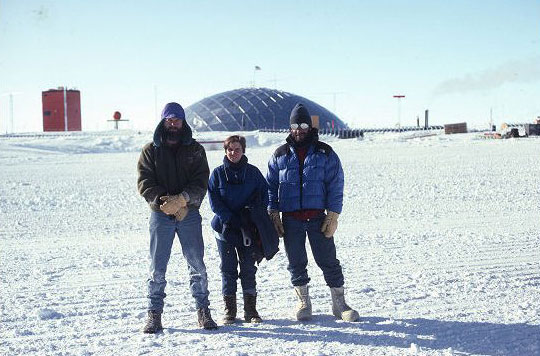

The team has extracted ice cores from some of the most inhospitable places on the planet, using both high-tech equipment and remarkably modest means. Mosley-Thompson uses specialized drilling equipment to probe Antarctic glaciers, whereas Thompson has retrieved samples from Kilimanjaro using a hot-air balloon and from the highlands of Tibet using yaks. In 1992, Thompson crossed the Gobi of Mongolia, terrain once frequented by the namesake of the Andrews award. During his trip Thompson hauled ice cores across the desert using ancient trucks; when the vehicles broke down, he used ice cream to cool his precious samples. Even when technology performs flawlessly, an added sense of urgency accompanies Thompson’s work: many of the prime icy records of climate in the equatorial mountains are vanishing at an alarming pace due to global warming.

Both explorers are well published in the scientific literature, but they also appreciate the importance of educating the pubic about current and future climate change and the effect of that change on our lives. Works of popular science (such as Thin Ice, by Mark Bowen, 2005) have helped publicize their research. In addition, Thompson entered the headlines in recent years when he called attention to the shrinking ice cap atop an African peak immortalized by Ernest Hemingway. Thompson predicted that the famed “snows of Kilimanjaro” will vanish by 2020.